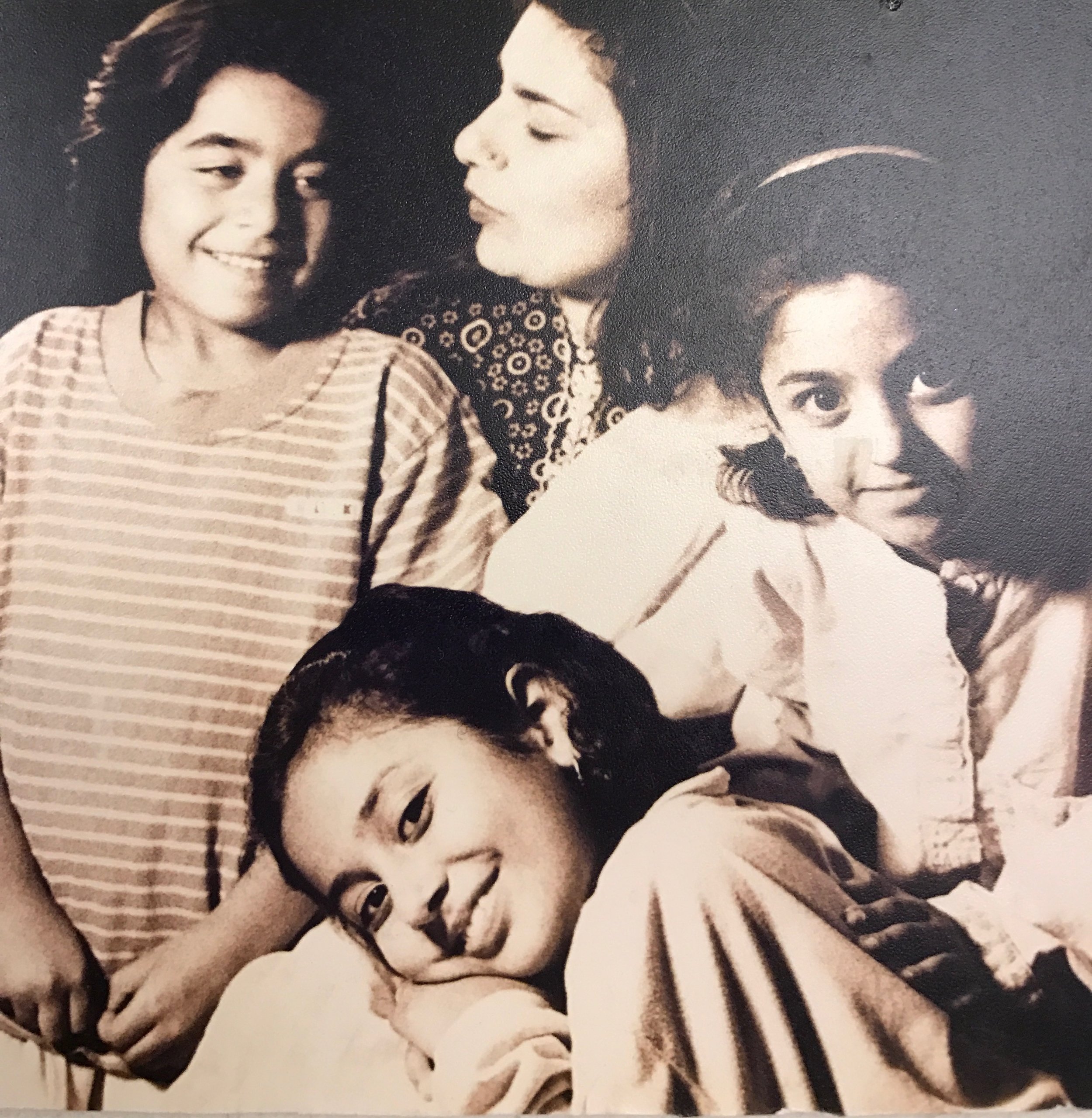

It feels odd to discover at this age and this stage in my life what it is like to share the ordinary details of my domestic life with my father. There was never a need to do this when my mother was alive. We had a WhatsApp group, “Noor Ladies Only,” that documented the everyday travails of three young women navigating their lives and kitchens in different parts of the world, peppered by their beautiful mother’s selfies. When I look back through that group chat, I feel very strongly that it is a powerful time capsule, capable of taking me back to her, the Urdu script of her messages showing her hope, her resolve to fight the disease that was slowly colonizing her body, her devotion to her family. The group is silent now. We are trying to fill the silence with noise in “Noor Siblings Only,” “Noor Sisters Only,” and “The Noors – Papa & Kids.” It’s the last group that surprises me most often because of the obvious need for its existence and the fact that this need was felt most acutely only after my mother’s death.

It never occurred to us to have a space just with our father when our mother was with us. When Mama was alive, we had a whole-family WhatsApp group, too, but no one ever used it. Once a year, someone would send a message for Eid, and then we would all forget about it. Strangely, sometimes I feel that in dying, our mother propelled us towards our father. Perhaps the force of love she always held tight to her chest was set free upon her children, and we, drowning in our despair came up for air and held on to our father. Our father, in his particular way, allowed himself to be pulled by the current while holding our heads above water. He, being the father that he is, saved his children from drowning without making a sound.

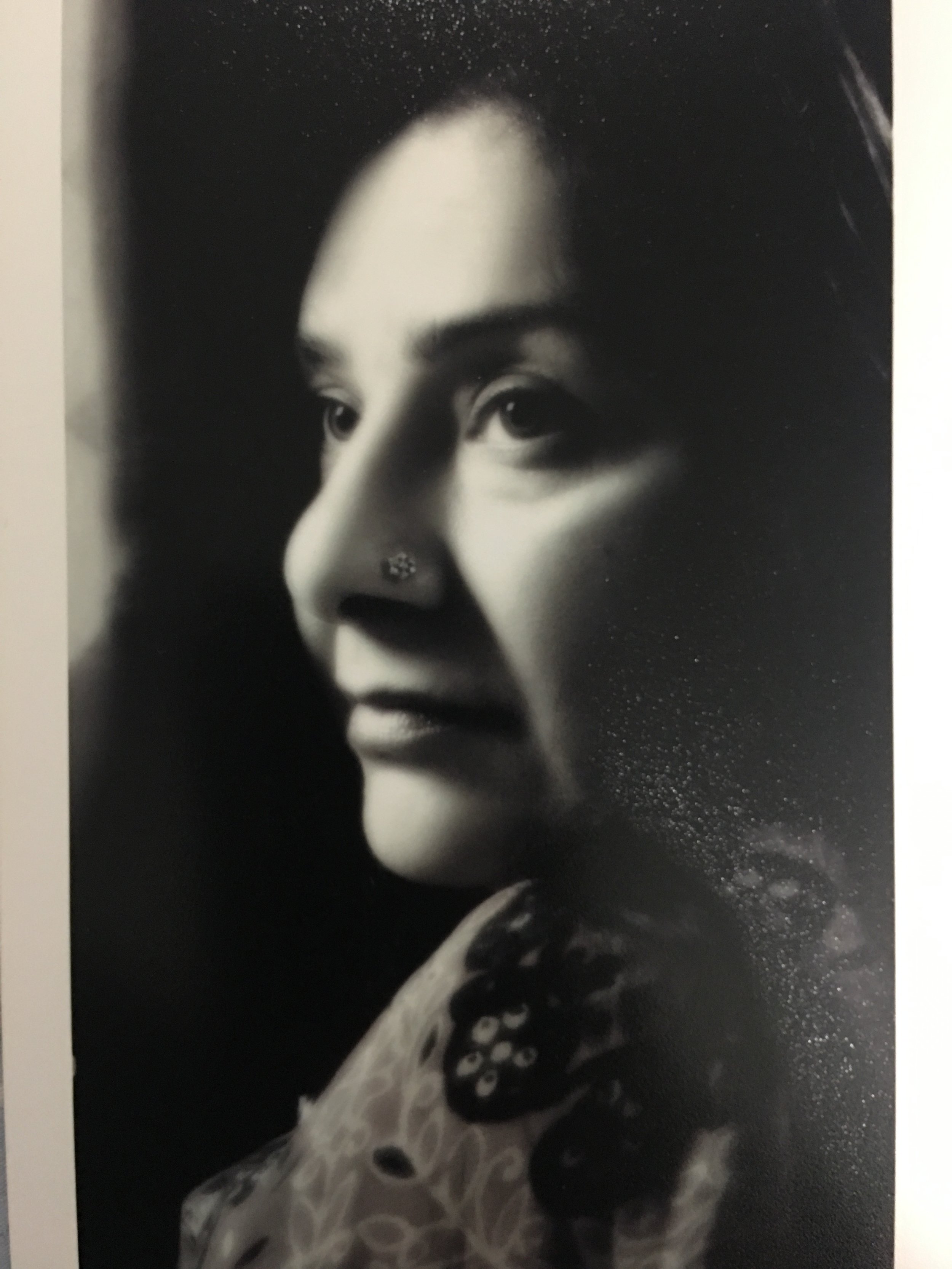

I don’t know what we gave back to him – perhaps something that should have been his for years already. An openness. An acceptance. A love that does not have qualifiers, complaints, or expectations – the kind of love my mother gave to him (and us). It is strange to love my father so fiercely again at 32, like the way I used to love him at 12 – with a single-minded devotion, with unquestioning respect, with a grateful sense of pride for all he had achieved in his life, with admiration for his life-long struggle to rise above his circumstances, to give his family a secure future, to fight fate, to pour himself into his art. How fascinating this man is – I realize – something my mother always said, but I never saw. “I find him admirable,” she would say. “He fascinates me. There isn’t a man I have met in my life who is quite like him.” I shrugged off her comments. Sometimes I rolled my eyes at her. “You’re hopeless, Mama."

But I see it now – it descends upon me like an epiphany, the meaning of my mother’s words. He inspires fascination and admiration in me, too. I see why I am the way I am – hungry for more, for lofty goals, for new avenues to prove myself, to make a difference and a positive impact. I have always been his daughter, but now I see how alike we really are. It took me a long time to purposefully forget this fact, and its resurfaced knowledge crashes upon me with a blunt indifferent pain. Who is my father and why was my mother so devoted to him until her last breath? Isn’t is utterly fascinating, the story of this young orphan, who fought abject poverty and his slated fate to be completely mediocre and forgettable, and instead achieved fame, fortune, and the highest civilian honor of his nation -- all because he dared to believe that he could do something extraordinary in life and then went on to demonstrate this belief in his art. My parents are those rare people who fed their family from their art. They loved what they did for a living, and for a while, they did it together. I, like my father, have always run towards what I love, tried to find contentment in my work, but have always been riddled with this certainty that there is more I could be doing, there is a lot more work to do. And so, like him, I keep searching.

My father, now 66, rises early, does not believe in vacation, and works constantly. When he is not working on his projects, he is working around the house. He likes to work with his hands on everything from assembling furniture to cooking. In our WhatApp group, “The Noors – Papa & Kids,” he sent pictures of turnip curry he cooked one afternoon in response to the culinary creations of his three girls and the street food adventures of his son. The frame was artistically composed in his signature style: the food presented in a clear serving dish, a pomegranate, an apple, and a grapefruit in a bowl next to it, a small box of milk, two rotis. The caption reads: “Made shaljam for my Rukhsana today and said a prayer for her. I hope the aroma of this effort reaches her. Ameen.”

This is how we live every day after her – a little high, a little low. Always we find each other, these five wandering souls – the Noor Papa and his kids.