On January 12, when I found out my mother had died, before she was declared dead by the emergency room doctors, before even the paramedics said there was no pulse, my immediate inclination was to deny it -- vehemently, violently. “Shut up and stop being an idiot!” I told my sister who had called from just a few towns north of me in California to tell me that our mother had collapsed suddenly in her home in Lahore, Pakistan. “I just spoke to her 15 minutes ago. She’s fine. You’re being dramatic,” I said coldly, intending to hurt her for her stupidity as big sisters are wont to do. My sister, God bless her, was surprisingly calm in a moment that can only be described as surreal. “I am not being dramatic. I am clam. Mama has collapsed. They are calling the paramedics. Ainee, are you there? Are you listening? Ainee, she’s gone, right? She’s gone.” It was the oddest sensation. I felt shut in, closed off. I went back to folding laundry, painstakingly, precisely, making neat piles as I eventually heard from the paramedics, then the emergency room doctor, and finally in the guttural, unbelieving voice of my brother that my mother was indeed no more. “Just get here, Ainee,” said my brother. “Just get here now!” As he was hanging up the phone, I heard him yelling at someone, “I am her son! I am her son!”

I didn’t break down until I sat at Dubai International Airport, waiting for my husband to sort out our 11-hour stay at the airport hotel. I was exhausted from our 16-hour flight from San Francisco, Jahan was dozing in my lap, and I was scrolling through Facebook, which had erupted with various notes, messages, and official and unofficial obituaries. And yet, it was a simple post that broke through the wave of detachment I was riding. My brother had posted an update to his friends, “My mother passed away. Will give you updates ASAP. Please pray.” Here was my 19-year-old brother living through an event that will certainly be one of the most harrowing of his lifetime, but to go through such a heartbreak so early, to bear this burden at such a young age -- how cruel, how unfair! And it was then that I thought of the unfairness of my mother’s death as it pertained to me -- how I had been cheated out of more time with her. Who, in this big vicious world, will love me now as she loved me? How lonesome and isolated I felt at that teeming airport with my own daughter safe in her mother’s lap still having the luxury to dream.

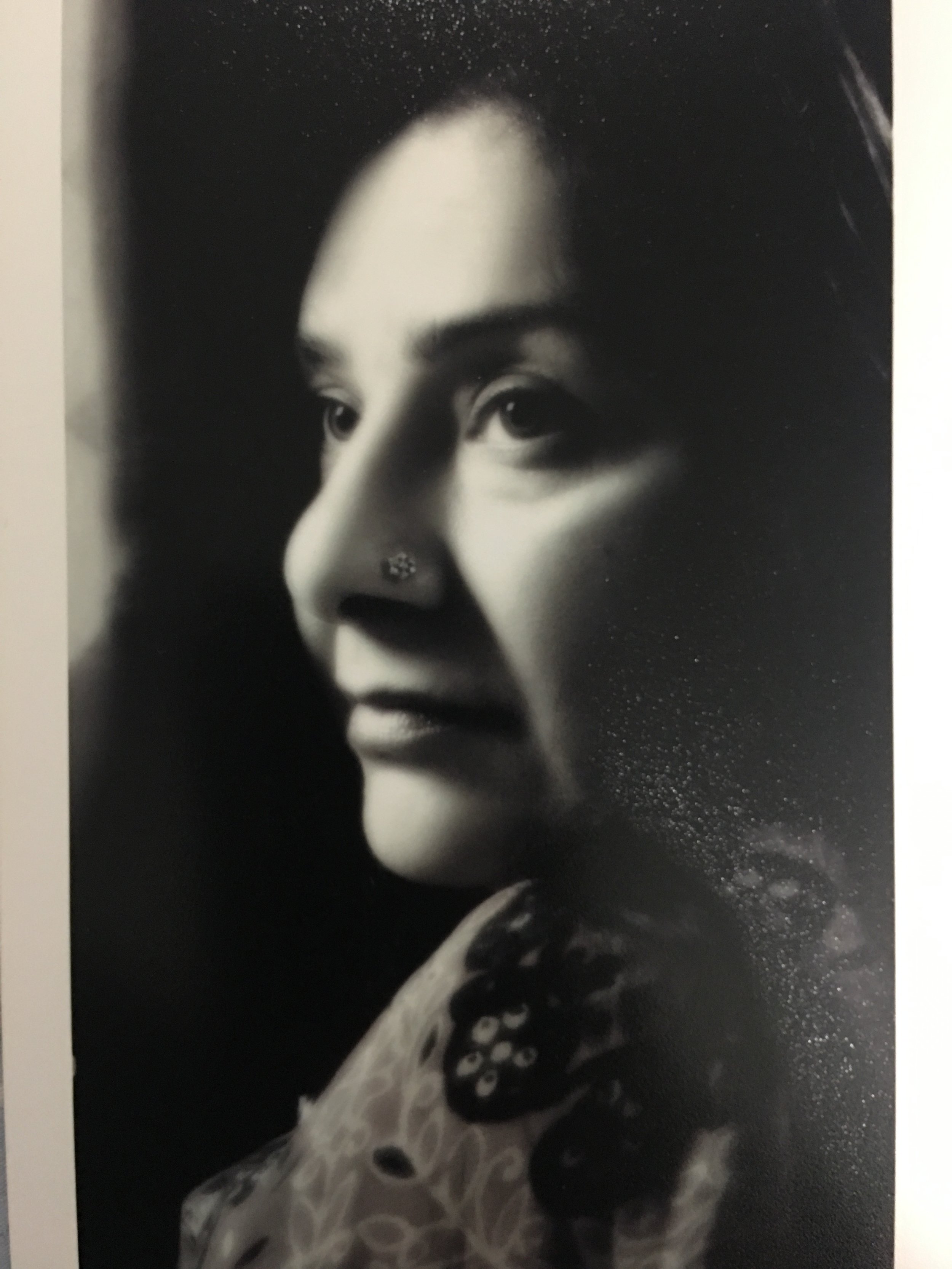

I wrote a lot about grief when I was writing regularly. Having read some of my older posts, I can tell that my anecdotal observations were not far from the truth. It hits you in waves, that part is true. It is harsh, unforgiving, brutal. What I didn’t appreciate was the power it imparts, like a vessel you harness to gain enough strength to kiss your mother’s cold, cold face, her soft eyelids, her shining forehead, her lips spread in a smile. You break and build yourself up again with every touch, you break and come together, break and come together until you are forever marked by your loss, marked by this gaping absence. There is a nakedness in this grief, the sense of being flayed open, laid bare for the world to see.

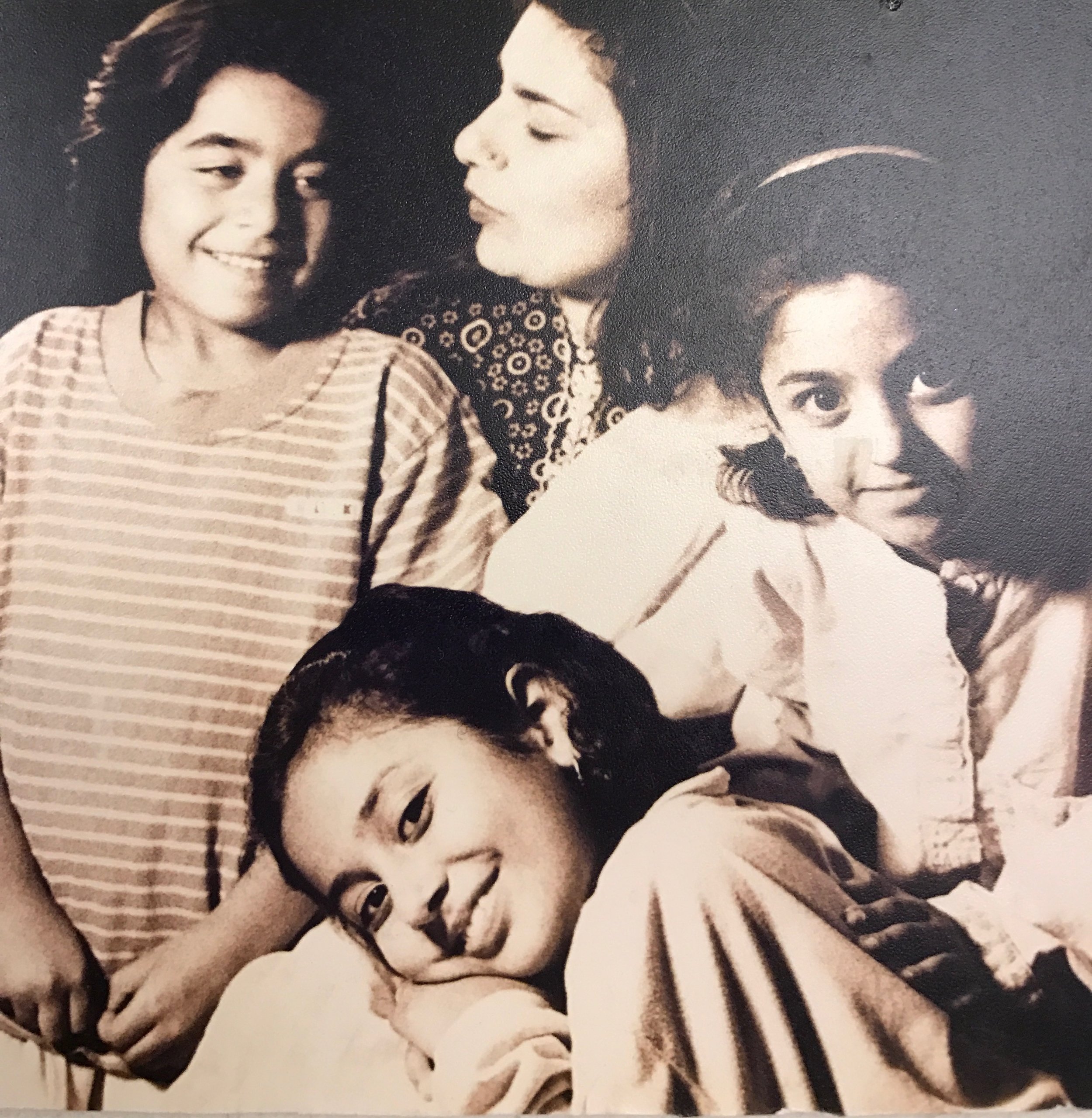

I am deeply uncomfortable with the lack of privacy that surrounds bereavement -- the way the family surrounds their departed loved one, gazing at their still faces, everyone around them wanting to offer comfort, to condole, to let them know how sorry they are, when all a daughter or a son would ever want at a time like this is to keep looking on at their parent’s face, to give them one more, just one more kiss, to touch their cheek, to say sorry, to say “I love you” over and over, and to finally, painfully, forcibly say good bye. When I reached the open verandah of Adil Hospital, Lahore, where some of the last rites were to be performed for my mother, I asked the other mourners, mostly other family members, to give me and my siblings a few moments alone with my mother. I wanted to be allowed the dignity to mourn in an enclosure of love and loss that is only shared by the four of us, her bereaved children. In these private moments, I allowed myself to be her baby, her first-born thirty-two year old daughter who is a mother herself, but still at the very core of my identity and existence, her baby. The four of us will remember these precious minutes as our deeply private and shared experience of heartbreak. And there is nothing more to be said about that.

It will take us the rest of our lives to make sense of this cruelty. Why, in the midst of such hope with her cancer shrinking and her health improving, did she have to be yanked away from us so suddenly; how could she simply cease to breathe when fifteen minutes before she was dozing and sleepily talking to her daughter and granddaughter; what could have caused such an absolute separation in a matter of minutes, seconds? But we remind ourselves that the deterioration of body and mind that is inevitable with a stage 4 cancer diagnosis was not something our mother withstood -- and for that, we are grateful. She, in a sleepy haze of routine post-chemo weakness, asked for her son, and then with her last breath uttered the name of the man she had loved fiercely and definitively since she was 24 years old. “Shah Gee,” she whispered to my aunt who was with her. “Shah Gee,” she said again before closing her eyes for the last time. And Shah Gee, my father, a man still seeking his magnum opus, a man who has loved his family thoroughly in his own way, but who has also worshipped his work, was on his way to Karachi airport after packing up his shoot for the day to fly to Lahore, planning to surprise his ill wife by appearing on her doorstep with his disarming smile, which is all she ever wanted. And this one time, fate betrayed my otherwise fortunate father as he rushed to the terminal and received my aunt’s call. My aunt placed the phone next to my mother’s ear, but she was already soaring to her final journey, her eyes quietly closed, not a sound emerging from her lips.