"Though there was no talk of it during this particular phone conversation, my father wanted me to be a dental hygienist. Unlike my sister, I wasn't shooting the lights out in school, and he thought it was essential that I have a practical skill to fall back on. A career in writing seemed about as likely to him as the chances of my inheriting Disneyland. My father thought I should be realistic."

- Ann Patchett in How to Read a Christmas Story. The Washington Post. Sunday, December 20, 2009.

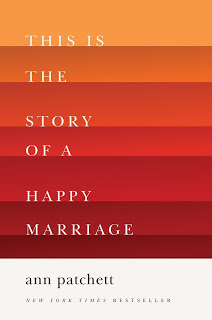

This morning on my drive to work, I started listening to a collection of essays by Ann Patchett that I have been meaning to pick up for quite some time. The book is intriguing even at the level of the title, which in my opinion, is hard to accomplish.

This is the Story of a Happy Marriage begins with a charming note by the author, taking the reader by the hand and walking her through the events and circumstances that made the book possible. A window for the reader to look in. The first essay in the book titled How to Read a Christmas Story originally appeared in The Washington Post in December of 2009 and is about the author being given an unlikely Christmas gift by her father, which she has cherished for many years. The gift was a story her father read to her over the phone on Christmas Eve. Listening to the essay, however, while I was moved by the gift of the story and how it still has meaning for the author after all these years, there was a different detail that made a deeper impression.

When one reads, one cannot help but become a part of the narrative, or bring one's observations, life lessons, perspectives, experiences, values, and philosophies to the reading. Why else would a book be resonant for a reader in one decade and completely jarring in another? I have experienced this for many books, most notably, The Catcher in the Rye and The Great Gatsby. Ann Patchett mentions in her essay that she intended to be a writer as early as age 6 -- remarkable -- and her family knew this, too. In the quote at the beginning of this post, Patchett reflects on her father's desire for her to be realistic and practical. Listening to this essay, I thought of my own childhood and how different it was compared to my adult life.

My father, too, was a man who liked storytelling, but he never thought that his children needed to be practical or realistic, because he never had those traits either. If anything, his lesson to us was, "Follow your heart, reality be damned." As a child, it was by turns exhilarating and confusing to be so removed from reality, to not be able to associate actions with consequences. I favored reading fiction, for instance, over studying for final exams. Our typical family bonding exercise was to watch a movie and take it apart scene by scene. My father could ask any number of odd questions. "Why do you think the camera was on a crane for this shot?" "Is this a set or a real location?" "Why do you think that telephone call was so important to be cut at that particular instant?" "Spot a continuity mistake in this shot." Finding a continuity mistake was like playing "Where's Waldo." Sometimes it was easy -- the actor had his sunglasses in the wrong hand all of a sudden. Other times, it was harder -- the ice-cubes in the glass had melted between two consecutive shots -- it took me about a quarter of an hour of rewinding and replaying the VHS to find this. When we couldn't watch a movie together, we would write. My father favored legal pads, my mother wrote on recycled newsprint sheets, I wrote in a wide ruled notebook. There was never a discussion in our house about being realistic, paying the bills, having a practical skill. It was like living in a bubble, which is why adult life, by contrast, was completely disconcerting.

I had to teach myself the practicalities of paying rent, for instance, when I first moved to California for college. For the first several months, I wrote instead of working. A weekly magazine that is no longer in publication in Pakistan, published the column I wrote: "Letter from California." Since I was not residing in Pakistan when I wrote the column, I was not paid for it. Eventually, the money my father had given me began to dry up. More would come for tuition and books, but I was beginning to discern the acute financial pressure on my parents, earning in rupees and supporting their daughter in dollars, and I wanted to pick up some of that burden. I kept waiting for something to happen, something grand and outrageous, the stuff of movies and stories. But nothing happened. I won third place in a local poetry competition, sold a couple of poems to small county magazines, and received a lot of rejections. A lot. It was a hard way to learn that I couldn't simply read and write and go to school and pay the bills. I was not a professional writer like my parents, but I never thought I had to be anything else in my life either. So, I got a job on campus. I began to pay attention. I realized I could do math! I fell in love with Biology. And for many years, I didn't write seriously. I cultivated the skills that are necessary to survive in the world. I anchored the dream-boat. I favored a lab notebook over a journal. And I became a realist.

Now, years later, my parents try to find the girl they raised together in me. My pragmatism scares them because they are not pragmatic people. They are artists and they have never known another way to be. They are those rare individuals who make a living from their art, who raise a family and tend a house all from an income generated by what they create. Their world is sustained by the world they craft on paper. I am in awe of them and in awe of the fact that I came from them. I am a writer in that I do not know how to be at peace with myself if I don't write, but that is the extent of it. Unlike Ann Patchett, I didn't give myself over to the destiny of a writer as a child. I didn't think I would be alone and poor because those are the hallmarks of being a writer. I also did not resign myself to the "Kafka model" Patchett mentions, banking on being discovered by virtue of my work after death. I wanted to do something now, in this life. I wanted to be a writer, but I didn't want it badly enough, and I wanted many other things, too.

So, here we are, twenty years removed from a ten-year-old who thought bliss is to be found only in the act of writing, the doors of creativity are always open, all you need is to pick up your pen and you will create something worthwhile -- probably because if there is anything my parents sheltered me from, it was from the travail of rejection, which they no doubt faced as all writers do. Last night on the phone, I told my mother, "These are the years. This is the time for me to work hard and have a career." My mother said, "I am proud of you, but work will always be there. This is also the time to take care of yourself." I said, "But my work is important to me." She said, "You and what you have to offer are the only things that are important." I just shook my head in silence and couldn't tell if she was speaking as a mother or as an artist.